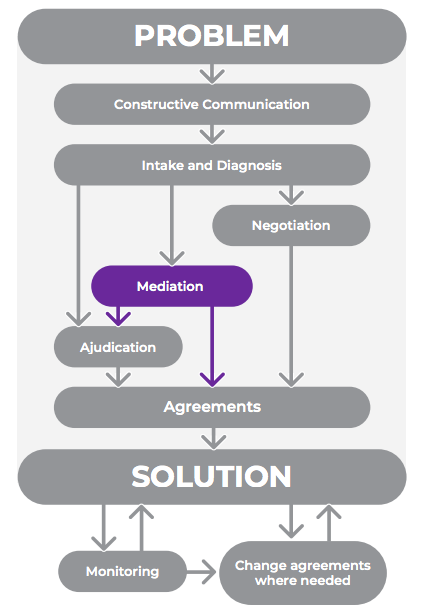

Mediation

Mediate if the parties cannot agree themselves.

From the intake and diagnosis it becomes clear whether mediation is possible. A prerequisite is that both parties must be willing to meet together in one room.

During mediation two parties meet together with an impartial third party (a mediator). Together the parties identify, discuss and make agreements. The mediator provides support, but does not make decisions for them.

International research points out that mediation process and outcome are perceived to be fairer compared to litigation.

Batabaganye singa enjoy ziba ziremereddwa okukkiriziganya nga zo

Okuva mu kuwandiisa n’okwekkenenya kiba kirabikirawo oba okutabaganya kunasoboka. Kkakasa nti enjuyi zombi netegekefu okwesisinkana mu kiffo ky’ekimu.

Mu kutabaganya, enjuyi ebbiri z’esisinkana wamu n’omuntu ow’okussatu atalina kyekubirira (omutabaganya). Olwo enjuyi ziteesa era ze zikola enzikiriziganya. Omutabaganya abayambako naye tabasalirawo.

Okunoonyereza mu mawanga amalala kulaga nti okutabaganya n’ebivamu kyangu ko era kya bwenkanya okusinga okugenda mu kkooti.

What practitioners say

Consistent with literature research:

How to get parties to mediate

Caucusing. As mediator, have separate talks with each party first. Explore their needs, with active listening and make them feel comfortable with the process.

Before starting mediation

Send invitations to both parties. Invitation letters should be given to both sides, clearly stating the goals, expectations and general overview of the mediation process. Since usually one of the parties brings the justice problem, there should be a clear message to invite the other party to come to the mediation.

Find a suitable mediator. The mediator should be impartial and promote a problem-solving approach. Both parties should feel comfortable with them. Factors such as age and gender should be considered if it affects the outcome of the process. Mediators should have sufficient training and experience, also in counseling.

Find a suitable location. Make sure the chosen venue is a welcoming and in a neutral setting that makes both sides feel comfortable.

Ensure accessibility. Both parties should be able to conduct the mediation in their own language and time, at an accessible location.

Ensure confidentiality. The mediator should ensure confidentiality of mediation.

During mediation

Explain the process. The mediator should take the time to clearly explain how the mediation will be conducted and what to expect.

Comfort. The mediator should make the parties feel comfortable with the mediator. The parties should trust the mediator.

Respectful communication. Ensure there is mutual respect between the parties and towards the mediator. Both parties should always speak calmly, not raising voices or making accusations.

Promote active listening. The mediator should ensure that both parties are listening to the other’s views. ∙ Focus on needs/interests. Bring the focus of the conversation towards identifying needs, not blaming others.

Give it time and space. The mediator should ensure that both parties are able to present their own needs and views at their own pace. Do not leave anything unsaid.

After mediation

Let the parties own the decision. Mediators should not impose a decision. The family members should be in full agreement.

Formalize agreement. An agreement should be clearly written and signed by both parties. Both parties should understand that this is a binding agreement and that there are certain consequences attached to that.

Other suggested practices

Make the parties feel welcome. As mediator, politely welcome both parties and make them feel at ease. The mediator should provide a “homely” environment.

Always look for win-win situations. Work towards agreements that make all parties happy.

Involvement of children. The views and needs of children should be taken into consideration. Sensitive topics, such as bedroom issues between the couple should be handled away from the presence of children.

Ziri ku mulamwa n’okunonyereza okuli mu biwandiiko:

Engeri y’okuletera enjuyi okutabagana

Ssisikana buli omu yekka. Ng’omutabaganya, sooka oyogerezeganye na buli luyi nga luli lwokka. Wetegereze ebyetaago byabwe, ng’obawuliriza obulungi baleme kuba na nkenyera kun kola eno.

Ng’okutabaganya tekunatandika

Ssindika obubaka obubayita bombi. Ebbaluwa eziyita enjuyi zombi zirina okubawebwa, nga zirambulula bungi ekiruubirirwa, eby’okusuubira mu n’engeri okutabaganya kuno bwekunatambula. Olw’okuba nti emirungi egisinga oluuyi olumu lutera okuleeta obuzibu mu bwenkanya, mulina okubeeramu akawayiro akalambika bulungi nti ayitiddwa mu kutabaganya.

Ffuna omutabaganya agya okusobola. Omutabaganya alina obeera nga talina kyekubirrira era ng’akozesa engeri y’okugonjoola ensonga. Enjuyi zombi zirina okuba nga tezirina buzibu ku mutabaganya. Ebintu nga emyaka gye, ekikula kye birina okwetegerezebwa oba binabeera ne kyebikosa ku binavaamu. Abataganya balina okubeera nga baatendekwa ekimala, ne mu by’okubudabuda.

Ffuna ekifo ekinakola obulungi. Kkakasa ng’ekifo ekirondeddwa kigya kukola bulungi ate ng’era enjuyi zombi tezikirinaamu buzibu wadde.

Okutuuka yo mu bwangu. Enjuyi zombie zirina okubeera nga zisobola okukwasaganya okutabaganya mu lulimi lwebategeera ne mu budde obubakolera, era nga n’ekifo kyangu kyakutuukibwako.

Kkakasa ng’ebintu byabwe bikuumibwa. Omutabaganya alina okukkasa ngg’ebikolebwa mu kutabaganya bikuumibwa mu bwekusifu.

Mu kutabaganya

Nnyonyola emitendera. Omutabaganya alina okutwala obudde n’annyonyola engeri okutabaganya gye kugy’okolebwamu na biki byebalina okusuubira.

Okuwulira obulungi. Omutabaganya alina okukakasa nti enjuyi zombi tezirina buzibu naye. Enjuyi zirina okumwesiga.

Okuwuliziganya okuweesa ekitiibwa. Kkakasa nti buli luuyi lussa mu munne n’omutabaganya ekitiibwa. Enjuyi zombi zirina okwogera obulungi bulikaseera nga teziboggokana oba okusonga olunwe mw’oli.

Buli omu alina okussaayo omwo. Omutabaganya alina okukakasa nti enjuyi zombi ziwuliriza bulungi omulala by’agamba.

Essira liteeke ku byetaago/ebibanyumira. Essira liteeke ku kutambuza emboozi ng’edda ku byetaago so ssi ku kusonga nnwe.

Kiwe obudde n’ebiseera. Omutabaganya alina okukasa nti enjyi zombi zirambulula ebyetaago byaazo n’ebyo byeebagala okwogera mu budde bwazo. Tokkiriza kintu kusigala yo nga tekyogeddwa.

Olubannyuma lw’okutabaganya

Okusalawo kakubeera okw’enjuyi zombi. Abatabaganya tebalina kubasalirawo. Ab’omu maka balina bonna okukiriziganya.

Enzikiriziganya etongozebwe. Enzikiriziganya erina okuwandiikibwa n’okutekebwako ebinkumu bya bombi mu bulambulukufu. Enjuyi zombie zirina okukitegeera ndi enzikiriziganya eno ebazingiramu era waliwo ebigyivaamu singa tegobererwa.

Ebirala ebiyinza okukolebwa:

Kkakasa nti enjuyi zonna tezirina buzibu na nteekateeka eno. Nng’omutabaganya, yaniriza enjuyi zombi bulungi era okakkase nti tebali ku bunkenke. Omutabaganya alina okubawa awantu awabajjukiza ewaka.

Buli kaseera nnoonya bombi webawangulira. Byonna ebikolebwa birina okubeera nga bisanyusa enjuyi zombi.

Okuyingizaamu abaana. Endowooza n’ebyetaago by’abaana birina okutunulibwa. Ebintu eby’ekyama ng’okweggata k’omwami n’omukyala tebyogerwa ng’abaana webali.

Kkozesa okutabaganya okwetegereza esonga. Okutabaganya okwetegereza ensonga kusingako okutabaganya okukolebwa okumaliriza bweziba nga nsonga z’amaka.

Resources and Methodology

Mediation is a commonly used intervention to resolve family disputes (Emery, p. 472 and Shaw, p. 447). Typically, the parties meet together with an impartial third party in order to identify, discuss and resolve their disputes (Emery, p. 472). The third party merely facilitates the process and does not make a binding decision for the disputants; unlike in a litigation process. In essence, the disputants negotiate their own agreement.

There is evidence available regarding user satisfaction with mediation and litigation processes and outcomes, children’s wellbeing and other factors (such as costs and time benefits).

Mediation is only considered an option for disputants who are willing to meet together. Mediation is most effective if there is a possibility to receive quick decisions from a third party.

For people divorcing, is mediation more effective than litigation for their well-being?

The databases used are: HeinOnline, Westlaw, Wiley Online Library, JSTOR, Taylor & Francis, Peace Palace Library, ResearchGate, Bloomberg Law and LexisNexis Academic.

For this PICO question, keywords used in the search strategy are: mediation, litigation, fairness, process, outcome, agreement, divorce, family.

The main sources of evidence used for this particular subject are:

- Lori Anne Shaw, Divorce Mediation Outcome Research: A Meta-Analysis (2006)

- Robert Emery, Divorce Mediation (1986)

- Linda D. Elrod, Reforming the System to Protect Children in High Conflict Custody Cases (2001)

- Joan B. Kelly, Family Mediation Research: Is There Empirical Support for the Field? (An Update) (2014)

The article by Shaw is a meta-analysis of various empirical separation mediation and litigation outcome studies. These studies deal with process satisfaction, outcome satisfaction, emotional satisfaction and understanding of children’s needs. Emery focuses on the court and consumer satisfaction with mediation, based on several empirical studies. Kelly’s article reviews multiple custody mediation studies, studies of comprehensive separation mediation projects and studies of child protection mediation.

The biggest source used for the evidence is the meta-analysis study, which falls within the highest category of evidence. The other sources rely on multiple empirical studies. The strength of evidence is graded as ‘high’ according to the HiiL Methodology: Assessment of Evidence and Recommendations.

Desirable outcomes

Generally, people are more satisfied with the mediation process compared to the litigation process and perceive mediation to be fairer (Shaw, p. 448 and Emery, p. 474). Mediation helps people to understand the point of view of their ex-spouse. The mediation process is perceived to be less biased, and more beneficial to the spousal relationship (Shaw, p. 450 and Emery, p. 474). It provides people with an opportunity to air their grievances and to understand underlying issues (Shaw, p. 449).

In terms of fairness of the outcomes, mediation agreements (for example, spousal support and property agreements) are perceived to be fairer than litigation agreements (Shaw, p. 449). For example, mediation empowers both parties to decide themselves the level of fairness within their own separation agreement, which results in a more satisfying outcome. This increases the chances of compliance with the agreements made, by both parties (Shaw, p. 465). Furthermore, parents consider the custody and visitation plans negotiated in mediation to be more desirable (Shaw, p. 449).

It has also been reported that mediation helps both parties to focus on the needs of their children. In the mediation process, parents understand children’s psychological needs and reactions better than in the litigation process (Shaw, p. 448). Parents feel that agreements made in mediation are good for their children (Kelly, p. 4).

Mediation participants are generally more emotionally satisfied than litigation participants. Resolving a dispute through mediation increases the long-term welfare of divorcing spouses and it minimises conflict (Shaw, p. 464 and Kelly, p. 5).

Undesirable outcomes

Parties in mediation may misunderstand the aim of this process. For example, there are instances where one party thinks that the goal of mediation is to save their marriage, while the other party’s view is on finalising the separation (Shaw, p. 449-450).

Furthermore, some mediation participants feel rushed and pressured to enter into an agreement (Shaw, p. 450).

Although most parents are satisfied with the outcome of mediation, around 15-20% of people are dissatisfied with the outcomes (Kelly, p. 5). There is a notable difference between mothers and fathers. Mothers tend to be less satisfied with the final agreement in mediation than in litigation (Shaw, p. 448).

It is worth mentioning that mediation can be inappropriate in high-conflict cases, especially for the female party. One of the parties might get harmed where the imbalance of power is too great, for example in cases of domestic violence (Elrod, p. 528). Mediation is not recommended for parental alienation cases, because of deceptive and manipulative tactics and the lack of mediator’s training for recognizing the undercurrents that occur when one parent’s interferes with the child’s relationship with the other party (Elrod, p. 528).

Balance of outcomes

In determining whether opting for mediation is better than litigation for the well-being of parents and children during a separation process, the desirable and undesirable outcomes of both interventions must be considered.

From the above evidence, the benefits of mediation outweigh those of litigation in most circumstances. Mediation is preferable as it helps parents to better understand the needs of their children. Moreover, the mediation process and outcome is generally perceived to be fairer compared to litigation.

Recommendation

Taking into account the strength of evidence and the clear balance towards the desirable outcomes of mediation, the following recommendation can be made: For families separating, mediation is better than litigation for their well-being.