Adjudication (decision-making)

A neutral decision-maker can help make decisions where needed

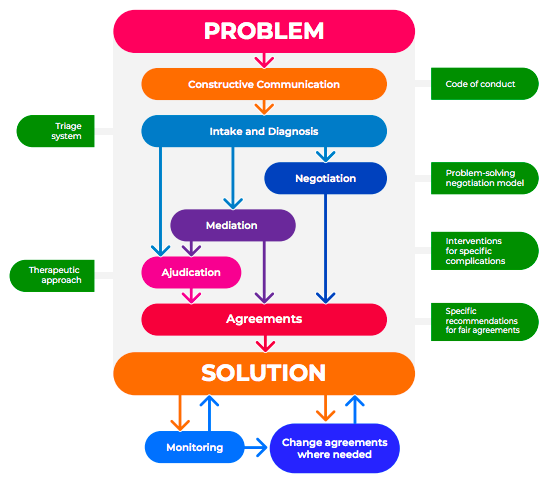

It is possible that the parties cannot reach agreement on all matters after negotiation and mediation. In that case, they need a neutral third party to get there. A problem-solving judge attempts to understand and address the underlying problem. The judge facilitates and creates the best environment for the parties to decide on agreements.

Such therapeutic approach to adjudication ensures a more comprehensive solution tailored to the legal, personal, emotional and social needs of the family members.

Omuntu atalina kyekubira asobola okuyambako mu kukola okusalawo singa kibeera kyetaagisiza

Kisobokera ddala okuba nti enjuyi ziremererwa okutuuka ku nzikiriziganya mu bintu byonna oluvanyuma lw’enteeseganya n’okutabaganya. Bwekiba bwekityo, betaaga omuntu omulala atalina kyekubira okutuuka yo. Omulamuzi agenderera okugonjoola ensonga agezaako okutegeera n’okunoggera eddagala ensibuko y’obuzibu. Omulazi ateekawo embeera enungi eganyisa enjoy okusalawo kunzikiriziganya. Engeri eno ey’okulamula eteekawo engeri y’okugonjoola ensonga ennambulukufu, nga erimu ebyetaago by’abali mu make eby’amateeka, eby’abantu, n’eby’eyo gyebabeera.

What practitioners say

Consistent with literature research:

Ensure neutrality. The decision-maker should be a neutral third party.

Explain the process. The decision-maker should take the time to clearly explain how the decision-making process works.

Communicate respectfully. Parties should ensure there is mutual respect towards each other and the decision-maker. Both parties should always speak calmly, not raising voices or making accusations.

Focus on needs/interests. Bring the focus of the decision towards the needs, not blaming others.

Formalize agreements. An agreement should be clearly written and signed by both parties. Both parties should understand that this is a binding agreement and that there are certain consequences attached to that.

Ziri ku mulamwa n’okunonyereza okuli mu biwandiiko:

Kkakasa obutekubira. Akola okusalawo alin’okuba nga teyekubira ku ludda lwonna.

Nnyonnyola emitendera. Akola okusalawo alina okutwala obudde annyonnyole mu bulambulukufu engeri okusalawo gyekukolebwa.

Okuwuliziganya okuweesa ekitiibwa. Kkakasa nti buli luuyi lussa mu munne n’akola okusalawo ekitiibwa. Enjuyi zombi zirina okwogera obulungi bulikaseera nga teziboggokana oba okusonga olunwe mw’oli.

Essira liteeke ku byetaago/ebibanyumira. Essira liteeke ku kutambuza emboozi ng’edda ku byetaago so ssi ku kusonga nnwe.

Enzikiriziganya zitongozebwe. Enzikiriziganya erina okuwandiikibwa n’okutekebwako ebinkumu bya bombi mu bulambulukufu. Enjuyi zombie zirina okukitegeera ndi enzikiriziganya eno ebazingiramu era waliwo ebigyivaamu singa tegobererwa.

Resources and Methodology

Test

According to the available literature, there is a distinction between two approaches to adjudication in cases of separation:

- An adversarial (or traditional) approach in a family context (where the judge only focuses on the parties and their legal dispute)

- A therapeutic approach in a family context, such as unified family courts (where the judge focuses on the family as a social system), characterized by a problem-solving judge

The adversarial approach is formal and only takes place within court. The main aim of taking an adversarial approach is truth-finding. It is a monopoly approach (instead of multidisciplinary) and its basic premises are post-conflict solutions, conflict and dispute resolution (Freiberg, p. 3). Taking an adversarial approach generally results in more claims of the parties (Miller and Sarat, p. 542) compared to a non-adversarial approach.

The goal of the therapeutic approach is to maximize the positive effects of legal interventions on the social, emotional and psychological functioning of individual families. The problem-solving judge is a critical actor in this endeavor. Rather than solving discrete legal issues [such as in the adversarial approach], the problem-solving judge attempts to understand and address the underlying problem and emotional issues and helps participants to effectively deal with the problem (Boldt and Singer, p. 91 and 95-96). The problem-solving judge embraces collaborative and interdisciplinary approaches. He motivates individuals to accept needed services (Boldt and Singer, p. 96). All legal actors involved in the therapeutic approach to separation are therapeutic agents, considering the mental health and psychological wellbeing of the people they encounter in the legal setting (Babb and Moran, p. 1063).

In some jurisdictions the primary role of family courts has shifted from [adversarial] adjudication of disputes to therapeutic approach (Lande, p. 431). For example, the unified family court system in the United States.

Unified family court systems are characterized by a holistic approach to family legal problems, an emphasis on problem-solving and alternative dispute resolution and the provision and coordination of a comprehensive range of court-connected family services (Boldt and Singer, p. 91). All matters involving the same family should be handled by one single judge (or judicial team) (Boldt and Singer, p. 96).

For people separating, is a therapeutic approach to adjudication more effective than the adversarial approach to adjudication for their well-being?

The databases used are: HeinOnline, Westlaw, Wiley Online Library, JSTOR, Taylor & Francis, Peace Palace Library, ResearchGate, Bloomberg Law and LexisNexis Academic.

For this PICO question, keywords used in the search strategy are: mediation, litigation, judicial, court-annexed, judge, decision, adjudication, needs-based, problem-solving,

The main sources of evidence used for this particular subject are:

- Richard E. Miller and Austin Sarat, Grievances, Claims and Disputes: assessing the Adversary Culture (1980)

- Nancy Ver Steegh, Yes, No and Maybe: Informed Decision Making About Divorce Mediation in the Presence of Domestic Violence (2003)

- Barbara A. Babb and Judith D. Moran, Substance Abuse, Families and Unified Family Courts: the Creation of a Caring Justice System (1999)

- Jana B. Singer, Dispute Resolution and the Post-divorce Family: Implications of a Paradigm Shift (2009) ∙ Andrew Schepard, Parental Conflict Prevention Programs and the Unified Family Court: A Public Health Perspective (1998)

- Peter Salem, The Emergence of Triage in Family Court Services: The Beginning of the End For Mandatory Mediation (2009)

- John Lande, The Revolution in Family Law Dispute Resolution (2012) ∙ Richard Boldt and Jana Singer, Juristocracy in the Trenches: Problem-solving Judges and Therapeutic Jurisprudence in Drug Treatment Courts and Unified Family Courts (2006)

- Bruce J. Winick, Therapeutic Jurisprudence and Problem Solving Courts (2003)

- Arie Freiberg, Non-adversarial approaches to criminal justice (2007)

Most sources used for the evidence are expert opinions. Some other sources rely on multiple observational studies. The strength of evidence is categorised as ‘low’ according to the HiiL Methodology: Assessment of Evidence and Recommendations.

Desirable outcomes

Based on its study on the unmet legal needs of children and their families, the American Bar Association has recommended the establishment of unified family courts in all jurisdictions. The problem-solving judge addresses the legal and accompanying emotional and social issues challenging each family. Informal court processes [such as mediation] and social service agencies are coordinated to produce a comprehensive resolution tailored to the individual family’s legal, personal, emotional and social needs. The result is a one-judge system that is more efficient and more compassionate towards families in crisis (Babb and Moran, p. 4).

Regarding unified family courts in particular

Survey respondents report that their unified family courts (UFC) are organized with broad-based subject matter jurisdiction over virtually all family-related disputes. Survey respondents report favourably on the use of the one-judge, one-family assignment system. Reasons given fall into two broad groupings; efficiency and therapeutic justice [or approach] (Schepard and Bozzomo, p. 336).

The Supervisory Judge of the Grafton County Family Division in New Hampshire expressed her belief that one judge per family affords consistency, accountability and ensures adequate and fair time for all concerned parties. An Administrative Office of the Court in North Carolina stated that the UFC model resulted in better case management, which ultimately led to speedy case resolution. The Senior Deputy Court Administrator for Family Court in the 20th District in Florida, stated that one of the greatest indicators of success of a UFC was empowerment of families by therapeutic justice, which enables families to be better off at the end of the process than they were when they entered the system (Schepard and Bozzomo, p. 336-337).

Undesirable outcomes

Evidence suggests that the ‘traditional’ adversarial approach to separation drives parents further apart, rather than encouraging them to work together for the benefit of their child (Schepard, p. 95).

Separating couples express overwhelming dissatisfaction with the adversarial approach to separation. According to a prominent study, 50% to 70% of litigants thought that the legal system was “impersonal, intimidating and intrusive” (Ver Steegh, p. 163). Another study states that 71% of parents report that the [adversarial] court process escalated the level of conflict and distrust to a further extreme. Separating couples were also dissatisfied because the process was too lengthy, costly, inefficient and not sufficiently tailored to their needs (Ver Steegh, p. 163).

Social science evidence suggests that, particularly for children, separation was not a one-time legal event but an ongoing emotional psychological process. Research also shows that the higher the level of parental conflict to which children were exposed, the more negative the effects of family dissolution (Boldt and Singer, p. 93-94).

Therefore, it is argued that, in order to serve children’s interests, family courts should abandon the adversarial paradigm in favor of approaches that would help parents manage their conflict and encourage them to develop positive relationships (Boldt and Singer, p. 94).

Regarding unified family courts in particular

UFCs promote therapeutic approach for families because they create a single forum to develop a plan for family rehabilitation without the specter of conflicting orders and proceedings. The Colorado court system recently has reported that as a result of a court structure that fragments family disputes between different courts. In a non-unified court system, different family members can end up in different courtrooms (Schepard and Bozzomo, p. 341).

Balance of outcomes

In determining whether taking a therapeutic approach to adjudication is better than taking the adversarial approach for the well-being of parents and children during a separation process, the desirable and undesirable outcomes of both interventions must be considered. From the above evidence, the benefits of a therapeutic approach outweigh those of an adversarial approach. The adversarial approach to adjudication is not satisfying the needs of people. Despite that the evidence in favour of the therapeutic approach is very low, the undesirable effects and their risks are also low.

Recommendation

For people separating, taking a therapeutic approach to adjudication is more effective than the adversarial approach to adjudication for their well-being.